Little-Noticed Activity in the Quitman Gap

And, To Tame a Land: The US Camel Corps.

Good Morning friends,

Current trends suggesting that the main focus of coverage for any major news organization should remain on the interior of the United States continue. There can be no doubt that cities like San Antonio, Denver, and Boston are looming large, as ICE agents and others continue trying to round-up and deport criminal illegal aliens.

This, plus the ongoing legal battles with activist judges trying to hinder deportations tend to obscure what is actually happening on the border right now.

This is as it should be, but here at the Dispatch we do try and zig while others are zagging. So, this morning we’d like to direct your attention to far west Texas— an area called the Quitman Gap, which sits in the middle of the Big Bend sector.

It’s not to be confused with Quitman, TX, over by Dallas.

In this case, the nearest towns of any size are Sierra Blanca and Van Horn to the East, and off the edge of the map below, El Paso to the Northwest. You can see, there’s a few landmarks sharing the name Quitman.

It’s basically a pass between two sections of the Quitman mountains. In Spanish, they refer also to the Sierra de los Lamentos, which is another nearby range in Chihuahua, Mexico. Apparently rock formations there create an eerie shrieking or moaning sound as the wind passes through them.

It’s probably one of the worst areas to try and cross in. So remote and inhospitable that Border Patrol’s never really had to staff it very heavily. Most traffickers and smugglers like urban areas where they can blend in and have more options on where to cross— areas like the Rio Grande Valley.

In a place like Quitman’s Gap, ICE and DHS can normally just park some cameras and sensors and call it mostly good. However, as of March, the Texas Military has parked some 200 soldiers in the Big Bend area, with plans for another 300 to follow-on, speaking to the concerns as local ranchers detect signs of smuggling traffic.

It should be noted, from January to February, crossings in the Big Bend area tanked some 71-percent, mirroring the effect the Trump election has had all along the border. That still amounts to about 165 encounters for February.

Sierra Blanca sits right on I-10, which is what makes this remote spot work for smugglers. Border Patrol agents manning the checkpoint there say they see about 10,000 vehicles daily.

This all comes as the US military continues shifting materiel to the border. Much is being made of the use of Stryker AFV’s. Normally, the armored fighting vehicles are packed with armed soldiers, an autocannon and machine guns, and sometimes anti-armor missiles.

But, for the border, the Army says they’ll be using them for long range surveillance and information gathering.

This all may remind some border observers of past incidents where the military was deployed to the Rio Grande.

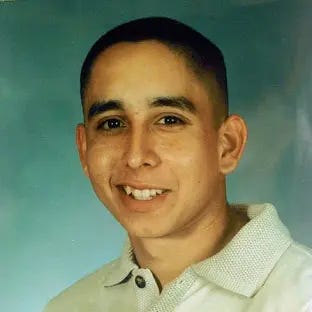

Back in 1997, 18-year-old Esequiel Hernandez, Jr— a sophomore in high school, was killed while herding his family’s goats near the town of Redford, smack dab in the Big Bend sector.

He was carrying a .22 rifle for wild dogs and other predators. Four Marines from Camp Pendleton in full ghillie camouflage were surveilling the area. The Marines reported trailing the boy, at a distance of about 200 yards.

The Marines reported Hernandez shot at them twice. Later analysis suggested he might’ve heard a noise or just been taking some target practice. Marine Corporal Clemente Banuelos fired once, hitting the 18-year-old under the armpit. He bled out, about 300 yards from home.

Texas Rangers say he probably never saw the Marines. The autopsy suggested he was facing away from them— and his rifle’s angle didn’t match their story.

Nonetheless, State and Federal grand juries cleared the Marines, calling it self-defense. The Marines were pulled from the border quickly— and the Pentagon paid the family a nearly 2-million-dollar settlement.

The Marines were attached to Joint Task Force 6, which was supervising all kinds of black helicopters and other military efforts along the river at the time.

Now might be a good moment to take a look back in Texas History— it was in March of 1855 that the US Army launched one of its more unfortunate and forgotten about experiments— importing Camels from the Middle East, with an eye toward testing them as possible replacements for draft horses and mules in the American Southwest.

The dromedaries and bactrians were mostly stationed at Camp Verde, in the Hill Country near Bandera, but would eventually see testing and other activity in various spots along what would become Route 66, all the way out to California.

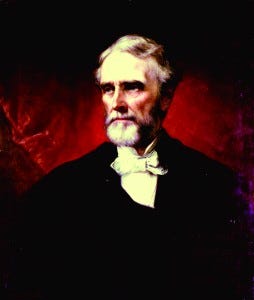

One of the champions of the program was actually Confederate President Jefferson Davis, who pushed for it in the pre-war years, convinced that it was a worthwhile experiment. At the time he was the Secretary of War for the Union. The initial investment was $30,000 Dollars.

By May, a ship was on its way to the Middle East. The USS Supply would return with its cargo of camels by February. They spent a little time in San Antonio, acclimatizing to the region, before setting out for Camp Verde.

Several tests would follow, and it quickly became clear that the camels were superior to mules— carrying more weight and needing less water and fodder.

A hostile test was later arranged, with a California militiaman, named Edward Beale. Beale was to survey a route from Fort Defiance, New Mexico to the Colorado River at the California/Arizona border.

It was 1857. The new Secretary of War, John B. Floyd, informed Beale he had to make room for Camels on his survey team. Beale wasn’t having it— objecting strenuously, but he wound up with no choice in the matter.

By the time Floyd finished relocating his camels from Camp Verde to Fort Defiance, he’d become a believer, writing to the Secretary:

“It gives me great pleasure to report the entire success of the expedition with the camels so far as I have tried it. Laboring under all the disadvantages ….we have arrived here without an accident and although we have used the camels every day with heavy packs, have fewer sore backs and disabled ones by far than would have been the case travelling with pack mules. On starting I packed nearly seven hundred pounds on each camel, which I fear was too heavy a burden for the commencement of so long a journey; they, however, packed it daily until that weight was reduced by our diurnal use of it as forage for our mules.”

—Expedition Leader Edward Beale, in a Report to U.S. War Secretary John B. Floyd

Beale’s love affair with the camels only deepened as they left the Fort and began the actual survey work:

“Sometimes we forget they are with us. Certainly there never was anything so patient or enduring and so little troublesome as this noble animal. They pack their heavy load of corn, of which they never taste a grain; put up with any food offered them without complaint, and are always up with the wagons, and, withal, so perfectly docile and quiet that they are the admiration of the whole camp. ….(A)t this time there is not a man in camp who is not delighted with them. They are better today than when we left Camp Verde with them; especially since our men have learned, by experience, the best mode of packing them.”

—Expedition Leader Edward Beale, in a Report to U.S. War Secretary John B. Floyd

The camels were apparently well-content to eat the brush and prickly cactus they found along the trail. At one point, the expedition went 36 hours, taking a wrong turn into a box canyon with no grass underfoot and no sign of water. The mules were said to be in a panic. But the camels stayed cool, and helped lead the whole group to water.

Eventually they made it to the Colorado river.

“An important part of all of our operations has been acted by the camels. Without the aid of this noble and useful brute, many hardships which we have been spared would have fallen to our lot; and our admiration for them has increased day by day, as some new hardship, endured patiently, more fully developed their entire adaptation and usefulness in the exploration of the wilderness. At times I have thought it impossible they could stand the test to which they have been put, but they seem to have risen equal to every trial and to have come off of every exploration with as much strength as before starting…. I have subjected them to trials which no other animal could possibly have endured; and yet I have arrived here not only without the loss of a camel, but they are admitted by those who saw them in Texas to be in as good a condition as when we left San Antonio…. I believe at this time I may speak for every man in our party, when I say that there is not one of them who would not prefer the most indifferent of our camels to four of our best mules.”

—Expedition Leader Edward Beale, in a Report to U.S. War Secretary John B. Floyd

Despite these glowing reports, the future of the US Camel Corp. was ultimately a star-crossed one. With the Civil War looming, the camels were forgotten about. Confederate troops were detailed to see to the herd at Camp Verde. The camels were used to haul salt and other supplies around San Antonio. The rebel troops apparently hated the job and hated the camels. Some were mistreated, others butchered, and in time the herd was ruined.

Other camels survived further west and were common sights for many years after the war, as they plied the trails of California, New Mexico and Arizona. The US Military sold them off at auction, deciding perhaps wrongly, that the experiment wasn’t worth following up on.

The last known surviving US Army Camel was an 80-year-old named Topsy. Topsy died in Griffith Park, Los Angeles in 1934, though there were reported sightings of other camels in the wild for decades, believed to be descendants of others that had been turned loose to fend for themselves.

The LA County Museum of Natural History has a great write-up about Topsy, here.

It was during this rough period that a young future General Douglas MacArthur spotted one. In 1885, MacArthur was all of five years old, living in Fort Seldon, New Mexico. He wrote about it in his memoirs.

“One day a curious and frightening animal with a blobbish head, long and curving neck, and shambling legs, moseyed around the garrison…. the animal was one of the old army camels.”

The memory of the US Camel Corp remains alive and well at Camp Verde, with restored facilities and historic displays.

As far as the border goes, however, the Camel Corp. is yet another reminder of the long history of missed opportunities and squandered hard-earned knowledge that one finds when studying the borderlands.

Longtime readers may recall us making the point when talking about the original Texas Rangers and how their hard-won experience in Indian fighting was wasted and squandered.

We can’t help but worry that Texas may too cheaply discount the value of the lessons learned over the last 4 years and withdraw too quickly from its recent role in policing the border in the absence of federal effort. It’s all well and good that ICE and DHS are making lots of noise and are seemingly ready to rock. But we can’t help but feel that the State may find itself once again in similar straits 10 or 20 years in the future.

One hopes that the knowledge and experience that’s been so hard won is retained somehow, institutionally. Realize— Texas military troops have been deployed in significant numbers for roughly 4 years now. Some have even moved to the area and live here full-time, in order to make it easier.

Discounting these sacrifices by simply dropping everything and forgetting about it all would be an ‘ignoble waste,’ much like the whimpering end of the camel experiment.

And on that note, we’ll call it a morning. We’ll probably be back much sooner than usual— we just saw a headline about fresh trouble on the border between Haiti and the Dominican Republic. Longtime readers can probably recall why that should be of interest:

Poverty In Haiti

The “bonbon te” is one of the sadder emblems of conditions in Haiti. A single, simple signal of just exactly why thousands and thousands of Haitians are willing to leave a region widely regarded as paradise— the Caribbean— and travel the length and breadth of Mexico risking the truncheons of Mexican police and Military, as well as the potential predati…

Until then— have a great morning and we’ll see you again soon. As always, no one should mistake this humble little newsletter for any sort of official communication from Kinney County, TX, despite our employment there. It is produced separately and without oversight. We mention this to remain in keeping with County policies re: social media.

Thank you for that detailed history of Jeff Davis' camels, which I read with a mixture of sadness and delight. You do important work, Matt. I might add that I remember reading somewhere years ago (probably in the '80s when writing my sourcebooks) that the last of the wild camel sitings took place in 1961.